Aridity Marks “Mellow” Canyon Loop

Confusion about water dominated our 2020 return trip to Dark Canyon Wilderness—and led to other problems on what we thought would be a fairly easy canyon hike.

Our first visit was in April 1985. The access road that crosses near famous Bears Ears had been snowy and mucky, so we hiked it—some 10 miles to Woodenshoe Trailhead. I remember a descent through pine groves, hiking along running water and (I think) annoying salt cedar in Dark Canyon.

In 1993 we did a loop in upper Dark Canyon with our 6-year-old daughter from Little Notch Trailhead to Scorup Cabin, and back up Horsepasture Canyon.

We remembered conditions during both trips as being wetter than on this visit. In 2020, there was periodic water in all three canyons, enough for the loop trip, but you needed to know when to fill up. We didn’t.

We did not expect drought in Utah after spring months spent in Arizona with wetter-than-normal conditions. David was also misled by online posts showing photos of wading in upper Woodenshoe and Dark Canyons. We realized later those were from exceptionally wet spring 2019.

And finally, a misunderstanding about where the water was. A Forest Service source had told David “it’s running at the confluence.” In retrospect, she meant the confluence of Dark and Peavine Canyons (which had water) but he expected water at the confluence of Woodenshoe and Dark Canyons (at Sundance Trail junction). He packed sandals for crossings.

Sandals definitely were not needed in May 2020. Canyons were mostly dry, with some pools and a few small channels easily hopped. We found large pools in a sandstone creek bed about a mile above the confluence. We soaked our feet but did not fill up our water capacity. Mistake.

We arrived at Sundance Trail halfway into the third day of our trip. The plan was to camp there, then hike Sundance Trail down Dark Canyon—which I had wanted to do since we first visited the area in 1985.

The confluence was bone dry. We went on up Dark Canyon in search of water, scouting every cottonwood grove in vain and ended up hiking 17.5 miles that day to a small spring. Despite a gentle canyon grade, crisscrossing the wash in steep sandy climbs made for an almost 8500-feet total elevation change for the day (an average of 475 feet per mile). That was toughest day in our week-long trip.

show more

Included in the Utah Wilderness Act of 1984, Dark Canyon Wilderness now encompasses 46,320 acres in a horseshoe shape with three canyons. Mesas and some cherry-stem roads are excluded. It includes colored walls of Cedar Mesa sandstone with arches, mixed-conifer/aspen forest near the rim, ponderosa pine groves, meadows, springs, seeps, and hanging gardens—some drying out. Life zones range from high country on the rim to arid desert vegetation in the bottom of Dark Canyon. Cliff dwellings and rock art remain from an Ancestral Puebloan culture. Ten trailheads from the Elk Ridge Highlands descend into canyons.

Our 2020 trip was intended to repeat our original 1985 loop trip. Arriving late afternoon from Phoenix, we drove a dry road that passed the famous Bears Ears and parked near Peavine Trailhead. Several loop hikers had signed the register. One noted, “it’s really dry in the back canyon” and suggested packing lots of water. We weren’t sure what was meant by “back canyon”—we found out the hard way he probably meant the main Dark Canyon.

After dinner, we hiked three miles of road to Woodenshoe Trailhead. Several vehicles here and register entries indicated four groups ahead of us. We hiked a well-used trail about a mile and camped on a ponderosa pine flat.

Next morning’s descent was quite pleasant through pines, green meadows, and wildflowers, with a few pools along the way. We found our first expected water at Cherry Creek 5 miles down. A new sign and tread indicated a trail up Cherry Creek not on our maps. After breakfast we followed this sandy trail about 2 miles towards spectacular red rock hoodoos, and through burned and remnant pine and marshy wet areas along the running creek.

Continuing on down Woodenshoe Canyon, David followed a side track to cliff structures with rock art while I elevated a tired knee against a tree. We met our first backpackers coming up. They’d hiked down ahead of us but turned back before the confluence with Dark Canyon.

We camped on a pine bench near pools of water and I enjoyed creating a camp kitchen on the rocky bench above the wash. The next morning the trail took us through a section right in the rocky wash for about a mile. We were confused by no water at what we thought was the Wates Pond area but we found water for breakfast in a pool beneath a pouroff just before the almost-dry Hanging Gardens.

On down, the stream ran in little channels through a marshy area, then dry areas, then deep pools in red rock. We neglected to fill up here, expecting water at the confluence with Dark Canyon, but even after the last dry mile we were still shocked to find no water there.

After a long afternoon hiking about 5.5 miles up the main canyon, we found a spring above the drainage (which was shown on the map). We also met Ben, a Forest Service wilderness ranger, camped by the spring. Exhausted by our long day, we filtered some water, set up our tent under a juniper just off trail, and went to bed without cooking dinner. (Ben had the best campsite for the rugged area.)

The next morning we filled up on water and talked to Ben, on his fourth season in Dark Canyon Wilderness. He said his boss had tasked crews to pull up and poison the roots of tamarisk (salt cedar). Perhaps that is why we saw so little. Ben said there was another spring about two miles up the canyon, then no water until upper Dark Canyon near its confluence with Peavine Canyon. He was quite accurate.

We stopped at Trail Canyon Junction in a nice pinyon-juniper campsite near large creek-hugging cottonwoods. Water was running just up the drainage. We decided to take a light day. We made the previous night’s dinner for breakfast, selected our tent spot for camp and set out on a day hike up Trail Canyon. GPS indicated 4 miles. I envisioned easy switchbacks to the ridge and back.

I was wrong. The trail was about 5 miles one way and only easy to start. The first mile ambled over to a wash and up a canyon with periodic water. Then the canyon narrowed and the trail steepened to a 700-feet-per-mile elevation ascent up sheer canyon walls with grand views of Dark Canyon below. We turned around at the trailhead and road to Elk Ridge. After a long descent, we both were tired. We had hiked 30 miles in two days, and David’s back hurt.

Half a mile up, the canyon had running water and was more like we remembered, but now lined with young willows (no salt cedar). Then it widened into a wash for a sandy five-mile slog. Then a corral and start of Peavine Corridor (road in wilderness). We passed the turnoff to Rig Canyon—once site of an oil rig—and continued up the road. We began to find pools and then running water.

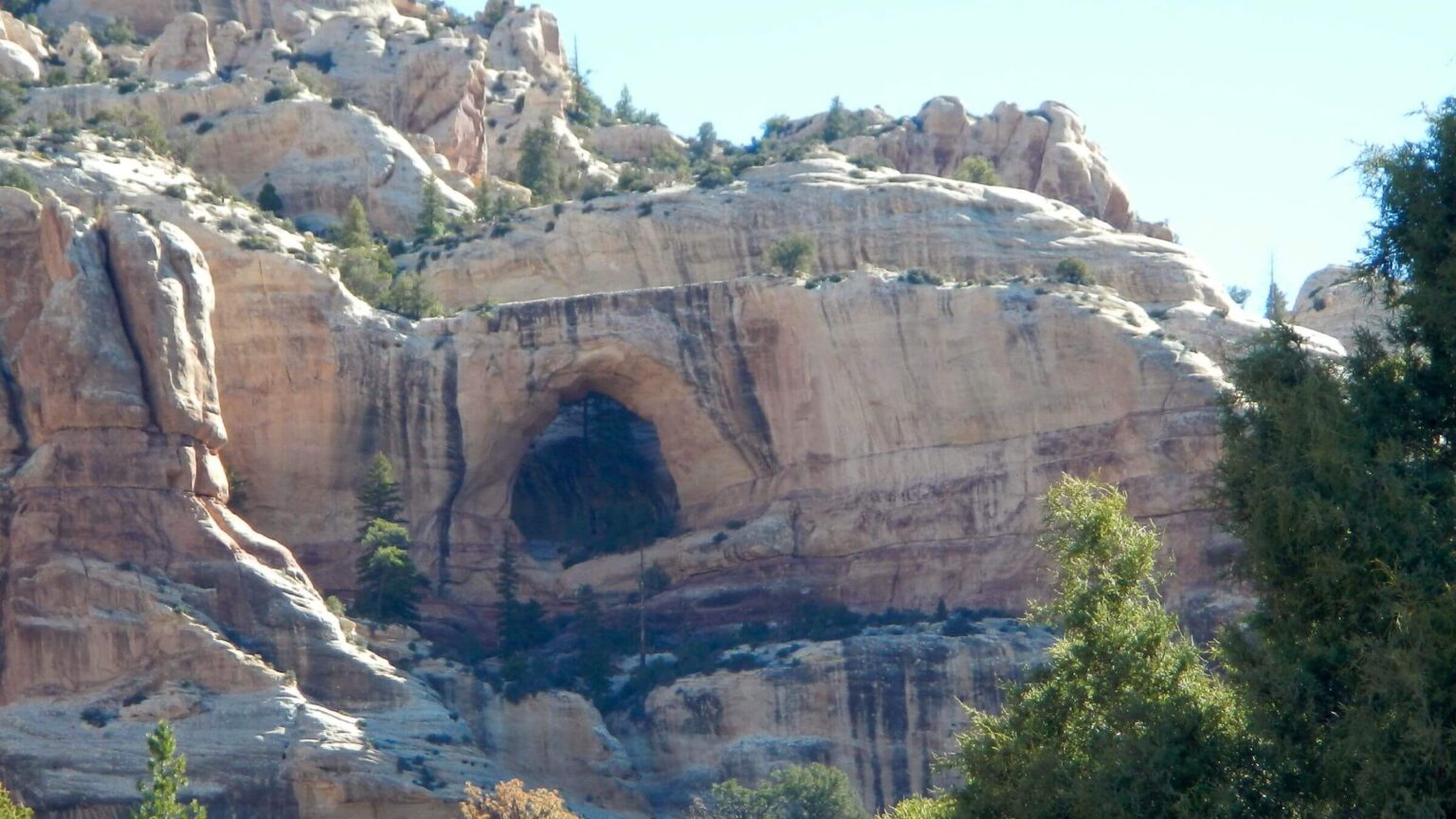

We camped early in a pine grove, took a bath, and then an afternoon nap. After dinner we hiked a half mile up to the Peavine confluence and back, passing a big arch on the canyon wall.

The rest of the trip was less stressful. We day hiked up Dark Canyon to Scorup Cabin, which we had visited in 1993. After sandy ups and downs the last section was marshy; water had inundated the old road and we skirted deep muddy tracks. A pouroff was running slightly; we have a 1993 photo of the same area with gushing falls.

The cabin was in good shape other than rodent poop. The register indicated visits from Notch-Horsepasture loop hikers, trail crews, rangers, and a few motorized users from Peavine. The green field below the cabin, more dilapidated than in 1993 photos, was probably farmed at one time; there were remains of horse-drawn farm equipment strewn around.

Just before we rejoined our backpacks at the Peavine confluence, we encountered an ORV parked in the road and two guys in a nearby field. David talked to the Forest Service range conservationist and assistant moving an exclosure (wire circular fence to compare non-grazed to grazed vegetation). They said that cattle would be turned out soon. They also noted that only one permittee family grazed the entire area; the senior member still rides the range packing an oxygen bottle.

The assistant, a local guy, said it was the driest he had seen in years. He thought Peavine Canyon would be dry all the way up and suggested packing water from the confluence. We did, but found water after two miles, and more water again near the top. A set of foot prints indicated another loop hiker had passed us during our day hike to Scorup Cabin. We never caught him.

During our slog up the dusty road we encountered several ORVs—we later learned it was the last weekend of the Utah spring bear hunt. The last vehicle was crammed with people, hound dogs poking heads out of box carriers, and two guys standing up like military guards. We were glad when the road left the canyon. We dropped packs where trail and road parted, checked out campsites and chose to camp in a small pine grove by the packs—sites on up were scorched by the 2019 Peavine Fire.

Our last half day and six miles were fairly nice. We found a spring and the creek later started to run as we passed through mixed-conifer and aspen forest, and green meadows dotted with blue lupine, pink phlox and, of course, the namesake yellow peavine! I was glad to see it before the cows were turned out to trample the area.

We met two groups: a family of five from Salt Lake City and two guys from California. I told both where to find water and where it was dry. The last mile was a steep crawl through gorgeous tall aspen out of the canyon to the trailhead, where it was chilly and very windy.

A reasonable hike but we managed to create ample challenges.

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking right arrow down/up.)