South Coast trek offers (too much!) water

For my 70th birthday on February 14, I suggested a backpack trip to celebrate. David marked his with a 70-mile trek in 2021, in Rincon mountains near our Tucson winter residence.

But Arizona was in serious drought with no water for backpacking. We sought a wetter option. The Condor Trail in southern California definitely offered that!

We chose part of this 400-mile trail through Los Padres National Forest near Santa Barbara because area had two good January rains, more was predicted, and local informants said two previous wet winters had recharged the watershed; most springs would be running.

David planned to hike Condor from Lower Manzana (near Nira) to Piedra Blanca trailheads through three wilderness areas. We would do part of 2008 loop we did on Manzana and Hurricane Deck to check out burn scar of 2007 Zaca Fire; rest would be new country. (We had also looped through charred pines in Dick Smith Wilderness south of the Condor in 2009).

A rainstorm was predicted for Day 2, and I worried about 33 miles of crossings on Sisquoc River. I suggested going up Manzana Creek to pine country above the river. But David wanted to follow the Condor route and thought storms might be windy and snowy up high (and we hoped to get to South Fork Guard Station Cabin for night of worst rain day). We went as planned. We had raingear, pack covers, and waterproof Sealskinz socks and gators.

On way to trailhead, we left bear canister with food and water for last part of trek at Deal-Tinta trail junction, then drove to Piedra Blanca Trailhead to park our vehicle and meet commercial shuttle for 3-hour ride to other end. But shuttle was late, delayed in part by highway crews repairing washouts; we started hike at 3 pm, much later than planned.

Nice trail and flat rocks on shallow crossings kept feet dry. I could sometimes glimpse white rocks of Hurricane Deck towering above us. We passed lovely Cold Springs camp but pushed on until dark to make up time; consoled by evening duet of two owls echoing in forest, bass answered by treble.

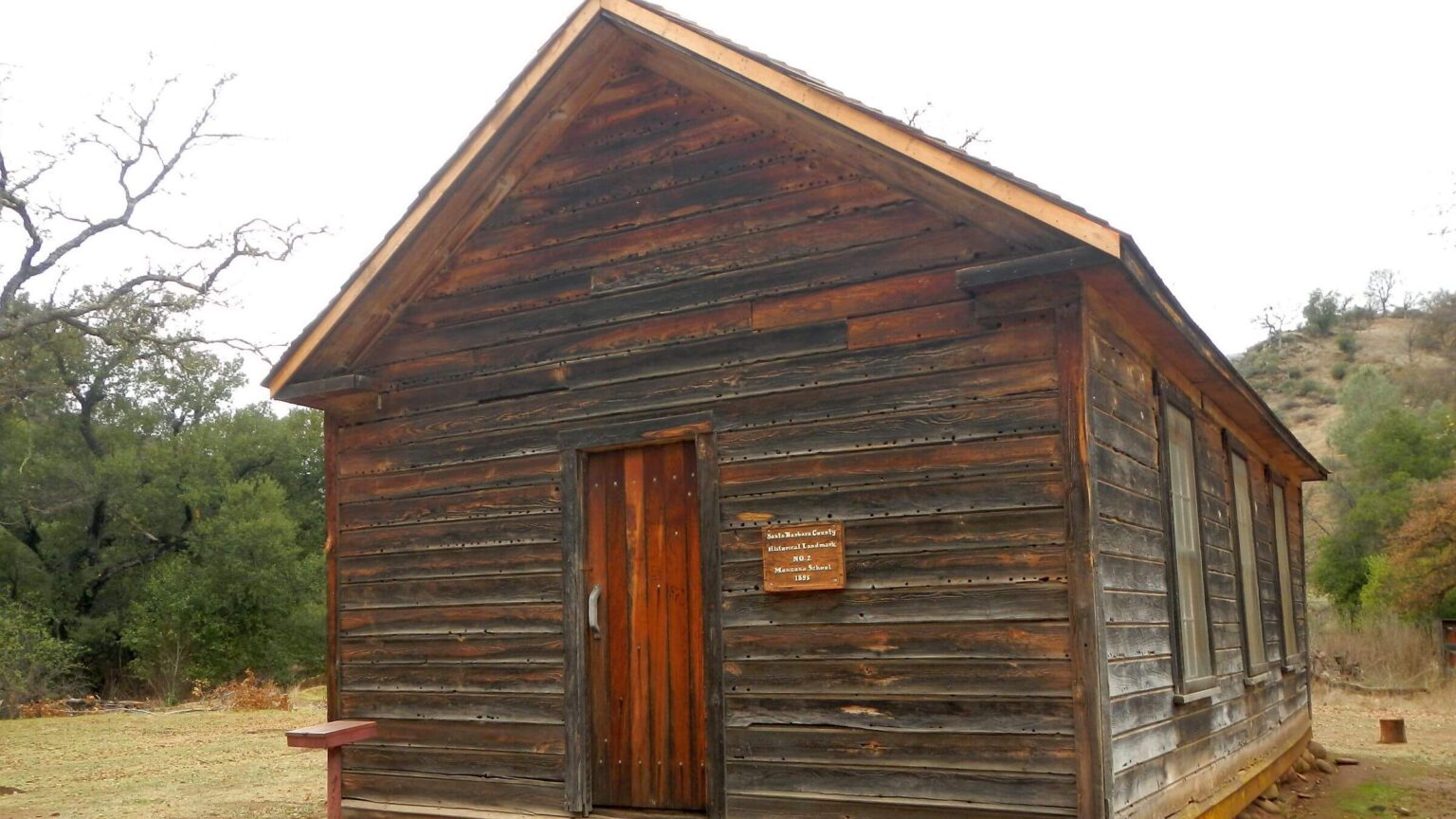

Rain started at 1 a.m. and was off and on throughout the day. Slightly cleared for break at Manzana Schoolhouse campsite—one of many camps with picnic tables, fire circles, a register and (in this case) even a privy—from era when Forest Service had funds for wilderness management.

We climbed to junction with Hurricane Deck then up to Sisquoc, shallow river that flooded frequently as indicted by rocky floodplain. Crossings were shallow with flat rocks but preceded and followed by much stumbling across floodplain rocks, except for a few hillside sections.

We camped in rain after 11.6-mile slog, dreaming of drying off the next night at South Fork Cabin, an old Forest Service guard station with a wood burning stove 17 miles upriver.

Instead, I spent the night 8 miles short of South Fork, huddled unclad in my sleeping bag, clothes soaked in surprise river rendezvous. Our trek had been abruptly halted by a surprise from the river.

Condor Trail in California South Coast ranges 400 miles across the Los Padres National Forest from Bottcher’s Gap south of Monterey to Lake Piru near Los Angeles.

We planned trek on southern part of Condor to traverse San Rafael, Dick Smith, and Sespe wilderness from 1100 to 7400 ft elevation.

Actual trek was altered because flash flood on Sisquoc River in San Rafael changed plans to a slightly shorter hike with more roads to make up for 2 nights waiting for water to recede. Trek included Manzana Creek and Sisquoc River (in San Rafael Wilderness); Sierra Madre Road, Santa Barbara Canyon, and Tinta Creek ORV trail (following boundary of Dick Smith Wilderness); and highway to Ozena Fire Station, Boulder Canyon, Reyes Peak, and Piedra Blanca Creek (in Sespe Wilderness). We stashed a resupply bear canister just before Ozena. We left vehicle at Piedra Blanca Trailhead and shuttled to Lower Manzana Creek trailhead near Nira.

California South Coast appealed for winter trek—unlike drought stricken southwest—because of ample water from January storms and lingering impact of two previous wet winters. Late winter is good for this area if minimal snow at higher elevations, as no ticks yet and nice daytime temperatures.

Three days of rain, however, was more than we bargained for. Two days frequently crossing shallow Sisquoc River went ok—until a flash flood caught us mid-crossing. Nearly chest-deep muddy water swept Cindy off her feet to float 350 feet downstream on her backpack! David helped her 7 minutes later off a rock she had stopped on in a shallow stretch.

Vegetation varied with riparian trees/shrubs on rivers and creeks, chaparral shrubs at mid elevations, evergreen oak forests in canyons, and beautiful pines and other conifers at highest elevations, including rare big cone Douglas-fir in a few places.

Trails were fairly good despite recent fires; only exception was last 2 days descending into whitethorn chapparal into and along Piedra Blanca Creek before meeting recent trailwork and crew coming up to do more. Many creek crossings but we were fine in hiking boots with water-repellant Sealskinz socks and Gore-Tex gators. Hiking roads and ORV trail were pleasant; no vehicles except during short highway section to Ozena Fire Station.

Sufficient water but we filled up at every opportunity and packed water for several dry camps. Most springs on map along trail were running.

Much solitude. Trail crew and day hikers last day were only people met in 10-day trek. Back-country roads still closed for winter. Cattle near Painted Rock, sadly trashing archeological site.

Visit statistics: 10 days, 100 mi hiking, at 2.0 mph, with 400 ft/mi of average elevation change.

Go to map below for more information on trailheads, daily routes, mileages, elevation changes, and photos. (Click on white box in upper-right corner to expand map and show legend with NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS.)

show more

Los Padres: on my bucket list since 2009

The Los Padres National Forest is almost 2 million acres along Coast and Transverse Mountain Ranges of central California—10 wilderness areas comprise 875,000 acres. It stretches nearly 200 miles north to south from Big Sur coast to the western edge of Los Angeles County. Elevations range from sea level to 8800 feet on Mount Pinos with riparian, semi-desert scrub, grassland, chaparral, oak woodland, coast, pinyon-juniper, and mixed conifer vegetation.I always wanted to hike more of the Los Padres. I was Santa Barbara district ranger from 2007-09 and was enamored by the forest’s 1200-mile trail system. But I had little time and mostly jogged trails near district office at San Ysidro Recreation Area and along the Santa Barbara front.

The 240,000-acre Zaca Fire, started July 4, 2007, by sparks from a grinding machine on private property, was contained on Sept. 4, my first day on the district. I was tied up with post Zaca problems—water officials’ concerns about potential mud floods and reservoir infill, citizens angry about one-year closure in burn area and rehabilitation projects. Summer 2008 belonged to Gap Fire which burned from top of coast range to Goleta, stopped by avocado groves, and costly “hydromulch” project to reduce erosion risk on front range. The November 2008 Tea Fire near Montecito burned 210 homes.

I day hiked with friends and did two backpack trips with David: looping part of Zaca fire scar in 2008 and part of Dick Smith wilderness on Santa Barbara Ranger District in 2009.

Our 2024 return skirted three wilderness: San Rafael, designated in 1968 after Wilderness Act of 1964, including Manzana Creek, Sisquoc River, the steep escarpments and wind-carved sandstone of Hurricane Deck, and the Sisquoc Condor Sanctuary for the endangered California condor a New World vulture and the largest North American land bird. Dick Smith, designated in 1984, with many creeks, rugged terrain, chaparral vegetation and mixed conifer on Big Pine Mountain and Madulce Peak. Sespe, designated in 1992, featured sandstone cliffs, wild and scenic Sespe Creek, a condor sanctuary and the Sespe Hot Springs. We had hoped to hike down Sespe to hot springs but ran out of time.

Peril on the Sisquoc

Third day of our trek was colder and wetter. After passing two more lovely camps, we stopped in trees to put on more clothes under our rain gear. A wool sweater provided warmth—until I slipped off a rock crossing the river and fell in! Still, wet wool was better than cotton and we kept hiking. Despite heavier rain, river level remained ankle deep for the crossings.Until it didn’t.

We had contoured far up a side canyon then on muddy, slippery section on steep slope above the river. I was slow clambering down slick mud route to a gravelly bar on the river and a crossing at some narrows. (We later realized the main trail went on the ridge; the drop to river was a wildlife route!) If I had been faster, I might have crossed river in time.

I followed David into ankle-deep river. Suddenly he yelled at me to hike upstream against the current. I did not see what he saw: a flash flood of muddy water racing toward us. I was suddenly in a powerful surge of chest-deep water and could not move (for details check “Sisquoc flood event” on map below, and uncheck all other boxes).

I took a step and was immediately swept downstream on my backpack. A ways down I fortunately hit shallower water, felt a rock below me, sat on it, and stopped! David made his way downstream, labored out to me, got my backpack, and led me to the shore where flood waters were rising quickly. We camped in an oak grove on in river bend that is actually an island in extreme high flow. I had lost a hiking pole, t-shirt, gloves, and pack cover; all of my clothes were soaked but my sleeping bag, food, and other gear in plastic was dry.

Light rain continued much of night with sprinkles into next morning—my actual birthday. But I got a nice present: my life was spared. Rain quit by late morning, so we dried stuff, made food, and explored. Water dropped and cleared by afternoon but still high, so we stayed another night.

Next morning we hiked 2.6 miles upriver with 10 calf-deep crossings and left the canyon at beautiful Sycamore camp on good trail that probably was road originally. South Fork Guard Station was still about 5 miles and 7 crossings upriver.

Steep climb afforded gorgeous views of the Sisquoc drainage and mountains beyond. On top, we spooked a herd of cattle and warily passed two watchful bulls.

David filtered water at developed spring tub while I sheltered from winds beside a battered line shack. We got to Sierra Madre Road and camped near cow-damaged Painted Rock petroglyphs.

Road on wilderness edge

Two 18-mile road hiking days went quickly. I was bummed at first by morning mud that mired boots; we walked beside road on brush and leaves for traction. I recalled Los Padres clay soils from my tenure there—once a field employee left her truck to plod down road on foot as mud was too slippery to drive!We skipped loop through Deal Canyon to get back on schedule and hiked Highway 33 to closed Ozena Fire Station in cold headwind with many vehicles passing. One kind fellow stopped to make sure we were ok. After dumping garbage, filtering spigot water, and adding warm clothes layer, we took Boulder Canyon trail short distance to camp in tall chaparral opening near Ozena’s boundary fence.

Pines at last!

One of my regrets was missing pine-topped Madulce Peak at 7600 feet, so I was glad we were ascending massive Pine Mountain. Misnamed Boulder Canyon Trail crossed dry creek once and then slowly contoured up and around hills and canyons to piney ridge. We dropped down old, uncleared trail to McGuire Spring to get water for breakfast and night’s camp. Old campsite near spring: a wood lined and covered box with some algae but fairly clear corner for filtering.Back at packs in sunny sugar pines we made breakfast, dried dew-drench tent, and fluffed down sleeping bags, then climbed through beautiful mixed conifer on Pine Mountain. Empty campsites and no vehicles on paved road—perhaps closed for winter.

Another water excursion down to Raspberry Spring on north slope trail with snowy crossings. Ugly camp but a pipe trickling enough to top off for camp and next day’s 10-mile hike on dry ridge to Piedra Blanch Creek. In pine-carpeted nook out of ridge wind we enjoyed fiery sunset and views of the coast 20 miles below with Channel Islands beyond.

What we thought was hike to Reyes Peak was just contour road to a saddle/ORV playground! We should have taken a trail that followed ridge to peak.

Trail southeast to Haddock Peak started on snowy north slope. Peak and some ridge were dry but descent to Piedra Blanca was snowy north slope and trail flanked with vicious whitethorn—snow slid me right into the barbs several times!

Finally, a ridge descent and contour into Piedra Blanca drainage. Lunch break at Haddock Camp, badly burned by 2016 Pine Fire and rather ugly. Trail was in poor condition for a national recreation trail! We saw tracks of a hiker who had slipped on mud a few days earlier. David made camp by large log in pine needle opening I thought was ugly because of scraggly brush and lots of lower dead branches on trees. After tent set up, I found a campsite with picnic table and fire circle in the pines—0.1 miles down the creek!

Next morning, 2 creek crossings then trail climbed out of creek, and crossed four side canyons before it dropped 2100 feet down North Fork to main drainage. At head of last canyon a side trail to “Pine Mountain Lodge” (named by hunters who built a cabin on the site in 1895, later destroyed) was flooded so we did not visit camp.

We hiked switchbacks shrouded in chaparral until we hit a section of nicely clipped shrubs along trail. Near bottom we met two guys from the Los Padres National Forest Association, the main volunteer trail group—marching up with loppers on their backpacks. They had cleared the trail section and were heading up to finish the job!

After break at Two Forks Camp, I waited for David at creek crossing. I lost a hiking pole in the Sisquoc and needed two to cross! This was last crossing; trail stayed above creek after this, passed more campsites, and then climbed over a ridge through the Piedra Blanca (Spanish for “white rock”) formation reminiscent of Utah canyon country. We saw a couple ahead of us and soon followed them across the ankle-deep Sespe River. We saw a couple ahead of us and soon followed them across the ankle-deep Sespe River.

At the trailhead, we met a friendly county sheriff on patrol. We were told that the trailhead was safe for leaving a vehicle and this seemed to prove it!

Checking later, water data (insert graph pdf) showed a huge spike in flows of the Sisquoc downstream same day I was swept downstream. We also learned that the Sisquoc is very prone to flash floods!

Next Los Padres visit I want more pines and less river. I want to hike from the Santa Barbara district to Mission Pine Basin and across piney ridges to Madulce Peak. David wants to visit South Fork cabin we missed. I am only hiking down the Sisquoc if there’s no rain forecasted!

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking left arrow down/up.)