Stark windy desert trek alone but near crowds & cars

Trekking plains and rolling hills through stark desert, wearing raingear against bitter winds from snowy mountains soaring to the west. Camping in the shelter of washes or rockpiles, huddling beneath a large juniper tree to cook out of the wind. Strolling through forests of Joshua trees. Sighting distant “Winnebagos” on the horizon and meeting hordes of hikers by every trailhead—yet camping alone every night. Black tree silhouette against pale peach and flaming red sunsets; camp bathed in full moonlight.

These are my memories of a 105-mile February hiking trip through Joshua Tree Wilderness.

An unusually cold, wet, and snowy winter in the West brought 150 percent snowpack to the 11,000-foot San Bernadino mountains rising above this desert wilderness north of Palm Springs and a few hours east of Los Angeles. This may explain why all but three days of our 12-day adventure featured chilly winds up to 20 mph even in the resort town of Twentynine Palms!

I had already been surprised by abnormally cold weather and frequent (but needed) rainstorms in southern Arizona where we spend the winter. I was looking forward to what I thought would be a warm backpacking trip in desert. (I had been spoiled by previous winter trips to Arizona border wilderness in elevations around 1000 feet. )

But most of our Joshua Tree trek was in Mojave Desert with elevations ranging from 4000 to above 5000 feet—and most of it was quite chilly.

After a harrowing day of rude commercial trucks and aggressive pickups on Interstate 10 from Arizona, lonely Highway 177 around the park was a welcome change—although we would have taken scenic Pinto Basin Road north across the park had we known it was paved! We found our way to 29 Palms Inn, where we left a suitcase for a mid-hike layover and resupply.

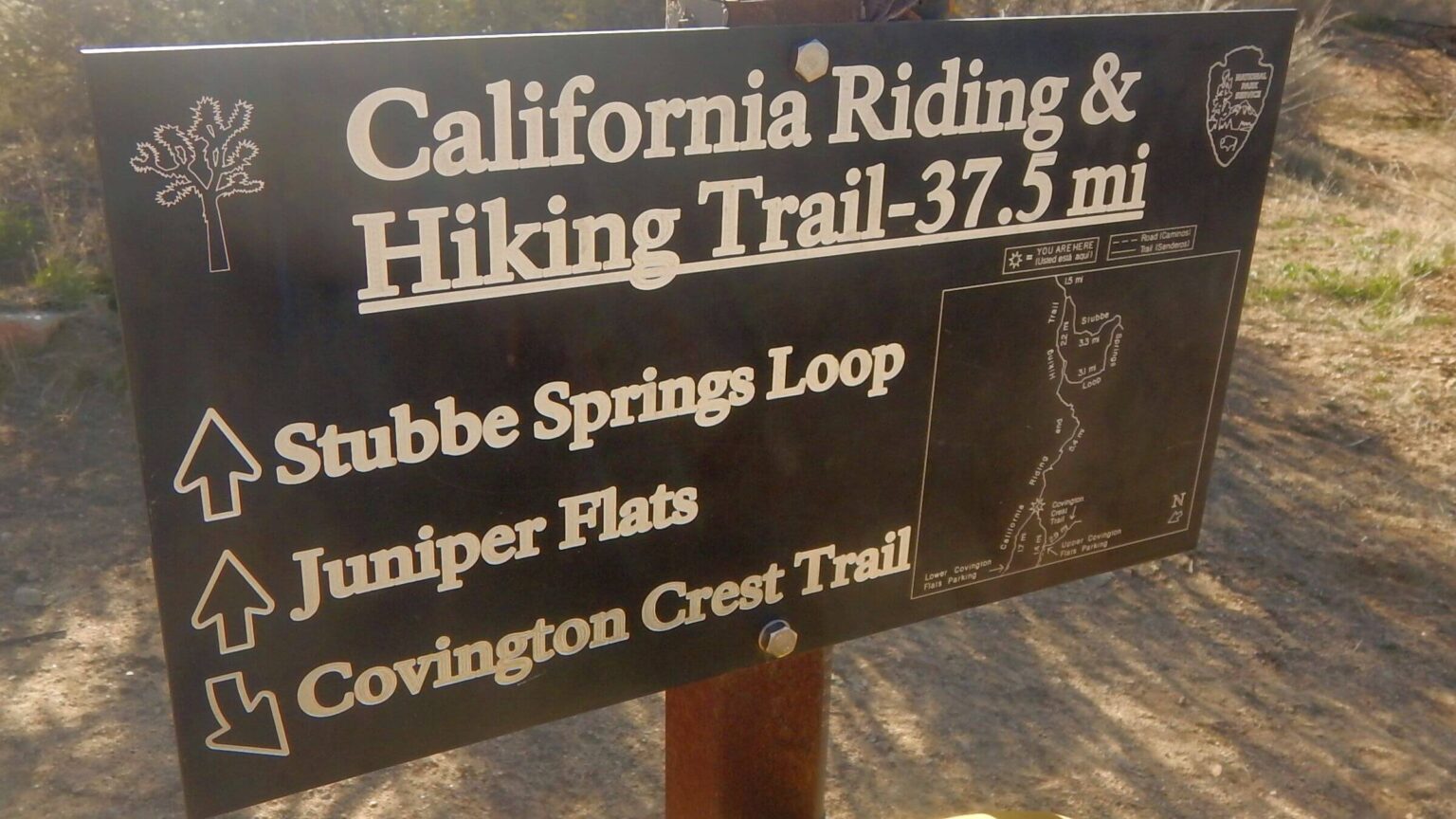

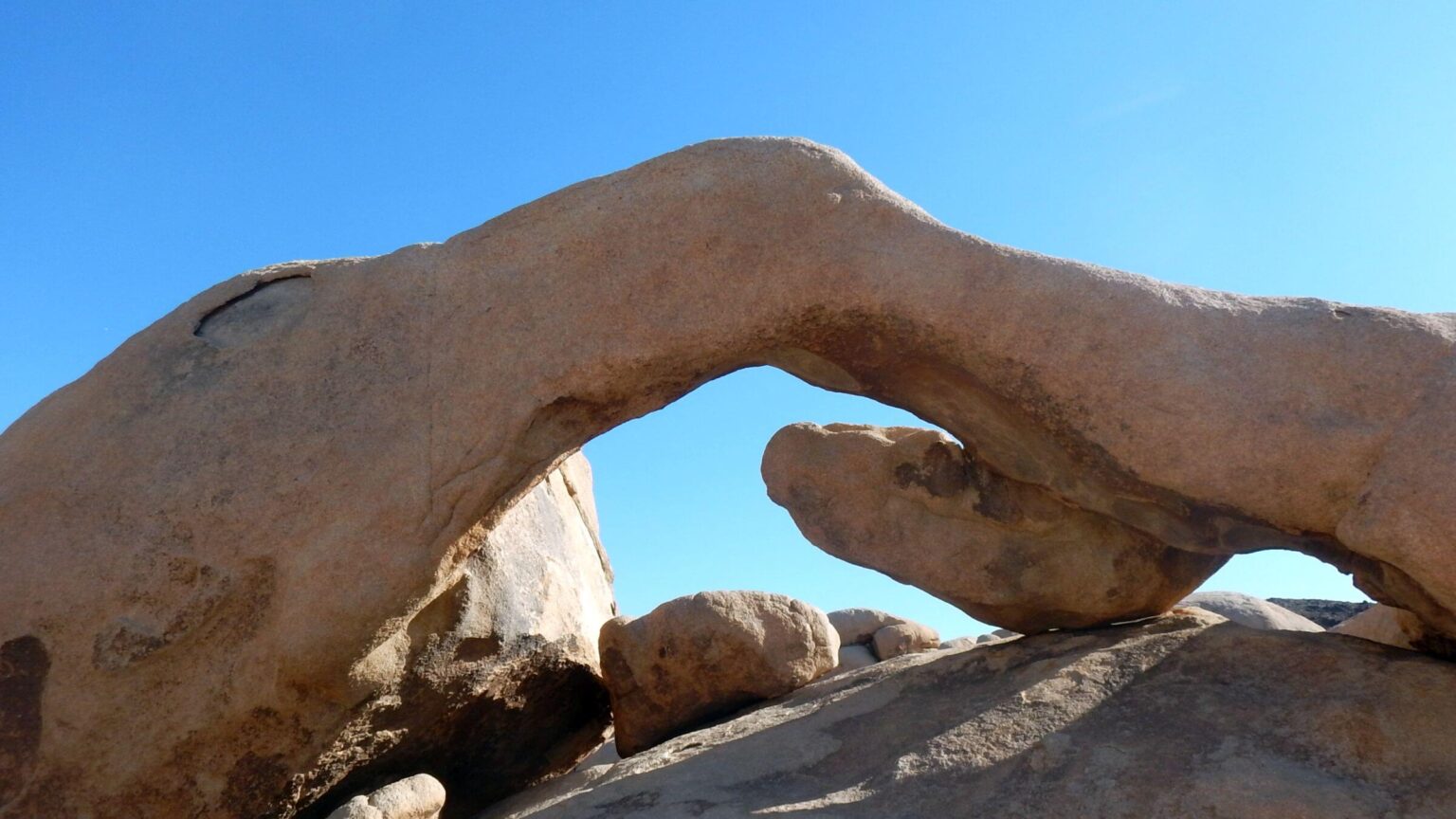

On a cool grey afternoon, we drove through north end of park to start placing our “water drops” near the CRHT, our core route. Stashing water behind large rocks near spur trail to the Arch and Windows, we joined crowds of day hikers; so many lined up that David postponed taking a picture of the Arch until our return a week later.

We left our hotel the next ice-cold morning to finish water drops; assaulted by gale force winds every time we left our vehicle. Cloud cover was replaced by dazzling white snow on the peaks west of us—perhaps the source of cold battering winds that met us on every ridge and high point.

Joshua Tree Wilderness covers 600,000 acres of desert in Southern California below towering San Bernardino Mountains and north of Palm Springs; comprises 85 percent of Joshua Tree National Park.

Forests of tall Joshua trees (treelike form of agave) and colorful rock formations are key features. Rolling ridges and valleys about 4000 feet up to volcanic ridges near 6000 feet in the northwest are Mojave Desert. Eastern parts mostly below 3000 feet are Colorado Desert, a subset of lower Sonoran Desert, with creosote, ocotillo, jumping cholla, and some Saguaro cactus.

There is no water for hikers in Joshua Tree Wilderness. Due to drought and higher temperatures from climate change, 60% of springs went dry between 2006 and 2016, the Park Service reports. We saw no springs or even potholes. On our first day we drove Park Boulevard (one of two paved roads in Park creating non-wilderness corridors) and Covington Flat graded dirt road to make seven “water drops”—water bottles placed under trees or bushes near trail.

Make backcountry reservations through unwieldy online recreation.gov site, reserving campsites in various zones. Or visit the park’s permit office weekdays at park headquarters in Twentynine Palms. (Tricky to find so call visitor center number (760) 367-5500 for directions and hours.)

Our 12-day trip (including water drop day, layover, and day hikes) circled northern half of wilderness counterclockwise from and to Black Rock Mesa Trailhead in far northwest; we hiked into town of Twentynine Palms for two-night stop and took cab to a trailhead to finish trek. We hiked 38-mile California Riding and Hiking Trail (CRHT), parts of Boy Scout and Bigfoot trails, and other side trails.

We met legions of day-hikers near every trailhead during our trek but only one couple backpacking CRHT in opposite direction. The last day (a Saturday) we met two groups and one couple backpacking, so it may be more popular as a weekend trek.

Visit statistics: 12 days (including stopover), 108 miles at 2.4 mph, with 325 feet per mile elevation change.

Go to map below for more information on trailheads, daily routes, mileages, elevation changes, and photos. (Click on white box in upper-right corner to expand map and show legend with NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS.)

show more

Joshua Tree human history

People have lived in the Joshua Tree area for at least 5,000 years including the Pinto Culture, Serrano, the Chemehuevi, and the Cahuilla. Cattlemen and miners came in the late 19th century, and white homesteaders arrived in the 1900s. Joshua Tree has 501 known archeological sites and 88 historic structures.Minerva Hamilton Hoyt lobbied to preserve Joshua Tree. After moving from Mississippi to California she fell in love with the desert but was appalled by careless destruction of Joshua trees and cacti. She founded the International Desert Conservation League. Noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead Jr. (designer of Central Park) appointed her to a commission to recommend new state parks for California.

Mrs. Hoyt wanted Joshua Tree to be national park. The National Park Service (Park Service) proposed a 138,000-acre monument but she pushed for more acreage. In 1936 President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the 825,340-acre Joshua Tree National Monument. In 1950 Congress transferred almost 290,000 acres back to public lands for mining and grazing. The California Desert Protection Act of 1994 returned this land to Park Service and designated Joshua Tree as National Park. Most of the monument became wilderness in 1976 with more acreage added in the Desert Protection Act and in 2009.

Although 85 percent of Joshua Tree is wilderness, we saw and even met motorized vehicles as our route passed near wilderness-exempted Park Boulevard, Covington Flat, the Geology Road and a spur road up Eureka Peak. We met no backpackers until last day of our trip!

Cold camps, late starts, sandy slogging

Our backpacking trip started with a very chilly camp on edge of the wilderness at Black Rock Campground. Our campsite reserved online was on a barren windy hill. Although the campground was only a third full and many sheltered campsites among big Joshua trees were unused, the rule-driven Park Service required camping in the site you reserved, no exceptions.So I took our cook pot, food, and stove and dropped down a hillside towards Black Rock Canyon, finding shelter from the wind beneath a big juniper tree, while David set up the tent.

I wore a turtleneck and stocking cap in my sleeping bag all night against the bitter windy night; my nose got cold if I put it outside the bag. Next morning, we stayed in the tent until sun hit it around 7:30. This would be our practice most mornings on this wintery desert hike.

At the trailhead I chatted briefly with two day-hikers who had hiked previous day and agreed the wind was outrageous (“I wore three layers all day,” she said). We followed them but parted company where we left the CRHT for a trudge up sandy canyons and side trails that eventually arrived at Eureka Peak—at 5,500 feet the highest point on our trip—besieged by gale force winds. This did not deter the photographer with tripod happily recording 360-degree views; I did not linger to chat but scampered down the road. We missed a trail turnoff and did an extra switchback or two, meeting two Off-Road-Vehicles before we rejoined the CRHT. We camped early by our first water drop, in a sheltered side canyon by oak and juniper trees.

Warm breakfast in the sunny nook and a milder day hiking down and up several low passes. I saw a bundled hiker far ahead of us whom we never caught. We left the main trail for side loop by dry Stubbe Spring. Day-hiker couple said they searched down canyon through willows and found nothing. After much sand slogging, we camped near top of a mesa and short spur trail to a great view of Coachella Valley and Santa Rosa Mountains 30 miles away on other side of valley.

Ryan rendezvous: many peak hikers

A warmer but grey day for our meet-up with my sister Chris and husband Dave who drove out from Oceanside to meet us. Two hours past our camp we met them on the CRHT and hiked back together to Ryan Campground, where they had parked. Weighted by a backpack, I struggled to keep up with younger pack-free kin! We saw many climbers on nearby rocks.Chris and Dave drove us all to the Ryan Peak trailhead, saving us a four-mile round trip road slog. We saw about 30 people on the steep 1.5-mile trail. First climb to small saddle included dozens of “stairs” up to 3 feet high—“check dams” installed by Park Service to prevent erosion that are not hiker friendly. My low back started hurting and I slowed down. Luckily, last stretch to peak was a gentle contour. Wind was nasty on top.

After our climb, Chris pulled out a Tupperware full of pumpkin squares—an early “present” for my Feburary 14 birthday. We took side trail to Lost Horse Mine (a gold and silver mine built in the 1890s) while our guests departed for home.

Our camp in an arroyo was hidden from the numerous day hikers visiting the mine. On way out next morning we saw more day hikers and discovered we were close to a trailhead on the main road.

Just before we regained the CRHT, I spotted the only backpackers on this leg of our trip, a couple headed the opposite way. We just missed them.

This day was flatter, easier, and warm enough to clean up with excess water from our next water drop. Cold weather meant we were using less water than planned.

One small new annoyance that persisted through the rest of the trip was presence of mountain bike tracks on so-called “wilderness” trail from Ryan Campground onwards; mechanical conveyances are banned in wilderness but either people are confused or don’t care.

Our camp in a bright orange rock outcrop offered wind shelter, spectacular sunset and full moon rise. For first time in the trip, I kept my nose out of the sleeping bag.

Wind returned the next morning to buffet all day and our last morning trekking into Twentynine Palms on Bureau of Land Management roads. A mile after camp we left wilderness; we paralleled the main road with campgrounds and busy trailheads all day.

We camped outside the park near our water drop in a wash on Bureau of Land Management-administered land. An evening walk towards a distant mine soon intersected with sandy roads heavily (and legally) used by local Off-Road Vehicle users with graffiti on rocks decrying Park Service “recreation.”

Windy break, a nice trail day—then wind returns

Our two -night break at historic 29 Palms Inn enjoying the beautiful oasis and palms on the sprawling resort and many restaurants in Twentynine Palms. Since we walked everywhere, we braved high winds most of the time, although we had the nice funky warm Bottle Room (to return from photo, click on text outside photo).Eschewing any more road hikes, we took a cab for the eight-mile drive to Boy Scout Trailhead and last leg of our backpack circuit. Climbing Park Service “stairs” into stunning rocky mountains, I soon was down to t-shirt and shorts—by far the warmest “wind free” day so far! We left the Boy Scouts via Big Pine Trail (named for a large dead pinyon pine at its end) and looped part of Maze Trail before camping in a rocky basin near our water drop.

Another cold windy morning for North View loop day hike—we met 10 hikers coming the other way, most in shorts (I assume it was warmer at their hotel!). After breakfast we crossed main road and took unmarked trail, eventually connecting with Panorama Trail along rim rock, then an annoying two-mile descent through endless sandy arroyos to rejoin Bighorn Trail in a wash.

Next morning, we looped on several trails to a rocky perch where a homesteader lived and wrote his philosophies on the rocks. Then up Bigfoot Trail for steep climb over 5000-foot Blackrock Mountains and eventually down to our water drop near Covington Road. Wind had picked up and we sought shelter in a grove of big juniper trees. Cold was paralyzing but sunset backdrop to Joshua trees was exquisite.

The cold blasting wind our last morning was mostly at our backs. After topping a long flat, we descended through washes by a few big pinyon trees, passing a few alluring side trails.

I was surprised to see a cheery group of young backpackers marching towards us into wind, excited for their 38-mile adventure (in two days) on the CRHT. It was Saturday; apparently most backpackers come on weekends. We met a couple with more leisurely agenda (to Ryan Campground), yet one more backpacking group, and several day hikers near the trailhead. (Including a couple groups with dogs, ignoring a kiosk message banning canines.)

Capstone for our visit was a 3.7-mile out-and-back (including some road hiking as parking lot was full) to famous 49 Palms Oasis with large native palms hidden in a canyon. Because the Park Service closed the area on weekdays (for trail reconstruction), it was packed out on the weekend with families and youth, dressed for hot weather. I had to trade my turtleneck for a t-shirt borrowed from David and zipped my pants to shorts in the sheltered sunny canyon.

The trail wound to a small pass then descended into a canyon, aided by Park Service “stairs.” On return we passed two summer-clad girls with a boy taking selfies on the pass. I headed down and noticed the trio following at my heels. I picked it up to a trot, leaving them far behind. After my last poor showing on Ryan Peak, bouncing down these “stairs” was a nice ending!

show less

Google Map

(Click upper-right box above map to “view larger map” and see legend including NAVIGATION INSTRUCTIONS; expand/contract legend by clicking left arrow down/up.)